The Winning Hand of Netflix’s House of Cards

People who’ve worked at the White House have a special gift. They can turn themselves into the biggest bores in the room by announcing to their fellow viewers of The West Wing or Scandal or House of Cards that what has just happened is (a) absurd; (b) ridiculous; (c) implausible; or (d) absurdly, ridiculously implausible.

To which the only appropriate response is: Will you please shut up?

I worked at the White House for two years in the 1980s, as a speechwriter to Vice President George H.W. Bush. So I possess this “special gift”—in spades. My wife is so fed up with my nitpicking that she no longer says “please.” In fact, she no longer says “shut up.” She just hits me. Who could blame her?

Politics can be—this will come as a shock, so brace yourself—a grubby business. But grubby business makes for splendid entertainment. After I left the White House, I wrote a bunch of satirical novels about politics and Washington, D.C. One, Thank You for Smoking, about a tobacco lobbyist, was made into a movie. In retrospect, these books may seem to pluck low-hanging fruit. It’s not that hard to make fun of politicians. They manage to do that all on their own.

But politics can also be—bigger shock coming, strap yourself in tightly—dull. So it’s no surprise that novelists, screenwriters, and TV scenarists often find themselves amping things up a mite.

My wife and I recently watched the first six episodes of Season 3 of Netflix’s House of Cards. And you know—she didn’t have to punch me once. Which isn’t to say that the series has suddenly taken a turn for the realistic. Far from it. But the fact that I’m able to watch it without grumbling tells me that I have achieved some sort of Zen-like satori, or enlightenment. It’s liberating, really. Go ahead, jump the shark. The bigger the shark, the higher the jump.

It would be churlish to give away too much, but I must mention one detail from an early episode: A Russian president who is the spitting, minatory image of Vladimir “the Terrible” Putin comes to D.C. for a state visit. And whom does he have sitting at his table at the White House state dinner? Pussy Riot.

You remember Pussy Riot—the Russian female punk-rock group, some of whose members were thrown in jail for daring to question Czar Putin’s idea of democracy? In an inspired bit of casting, two members of Pussy Riot play themselves. The premise behind this seating arrangement is that President “Petrov” has actually requested to have Pussy Riot at the table. And even to have a photo op with them, so the serfs back in Russia will think him broad-minded (as it were). Hmmm. Let us pause to ask ourselves: How likely is this? The point of having Petrov come to Washington, by the way, is to get his cooperation in a Middle East peace initiative.

But wait! I’m having another moment of satori! Now I get it: The real implausibility is the whole concept of peace in the Middle East! That sound you hear is my one hand, applauding House of Cards.

The episode is dramatic as can be, and wonderfully satisfying, even as it pirouettes from one oh, puh-leeze implausibility to the next. The subsequent episode centers on a reciprocal visit by President Francis Underwood and First Lady Claire. Its conclusion will leave you gobsmacked, as they might say in the original British version of House of Cards—muttering to yourself “Whoa!,” even as your Inner Implausibility Meter is going, “Weeooweeoo!” like an amok carbon dioxide detector.

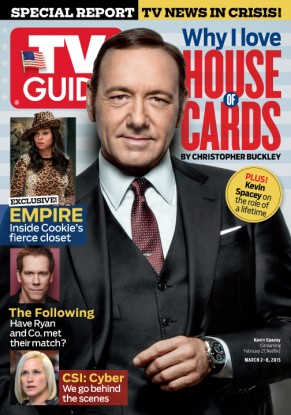

The president and first lady are—of course—played by the unimprovable Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright. Spacey is without equal as a villain. We met him in Season 1 as a South Carolina congressman, and by the end of Season 2, he had connived and murdered his way to the presidency of the United States. (Is this a great country or what?)

Spacey’s Underwood may be the role of his lifetime, but Spacey is still young (55), so this prediction seems, happily, unlikely. His performance is nothing short of mesmerizing. You find yourself cheering him on, even as he sinks to bathyspheric lows. Here is Faust, eatin’ ribs.

And why is it that Southerners seem to make the most entertainingly venal politicians in political dramas? Remember Sen. Seabright “Seab” Cooley from the 1962 film of Allen Drury’s Advise & Consent? He was played to rumpled, seersucker perfection by Charles Laughton. Most famously, there was Willie Stark in Robert Penn Warren’s masterpiece All the King’s Men, based on Louisiana Gov. Huey P. Long. Broderick Crawford portrayed him in the 1949 film with hearty, convincing menace—and very human vulnerability. We loved these guys even as we raised our eyebrows and murmured, “Oh, dear!”

I don’t know the answer. Maybe it’s the zest these good ol’ boy scoundrels bring to their roles. They just seem to revel in their wickedness. Yankee politicians at least take the trouble to look guilty.

The original British House of Cards, from 1990, was notable for breaking the fourth wall: The lead character turns and addresses the viewer directly, with the other players unable to hear what he’s telling us. It created an intimacy between us and Ian Richardson’s chilling Francis Urquhart. Urquhart was a silkier villain than Spacey’s earthy (if slick) Underwood. When he spoke to us, it felt as though we were being addressed by Mephistopheles himself.

The elimination of the fourth wall in the American House of Cards makes the intimacy all the more intense. The very first scene in Season 1 begins with Underwood addressing us as he strangles to death a mortally wounded dog on the sidewalk. This takes “You had me at hello” to a whole new level. Right away, we—and poor Toto—understand we are a very long way from Kansas.

Spacey once told an interviewer, “I think people just like me evil for some reason. They want me to be a son of a bitch.” Before he began shooting Season 1, he was on stage at the Old Vic in London in the title role of Richard III. House of Cards executive producer David Fincher told Spacey that would be “great training” for playing Francis Underwood. Yep, I’ll bet it was.

Spacey won a Best Actor Oscar for his performance as a middle-aged husband and father who develops a sexual obsession for a teenage girl in 1999’s American Beauty. But he’s essentially a good man who is redeemed in the end by paying a terrible price. There’s a core of decency inside Underwood, but the way things are going, by the time House of Cards folds its final hand, we’re going to need an MRI to find it.

I relish Spacey most when he’s playing an SOB: the vicious movie studio boss in Swimming With Sharks; sadistic office manager in Glengarry Glen Ross; small-time con artist Verbal Kint in The Usual Suspects; and killer antiques dealer Jim Williams in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, where his Southern accent was more bourbon than Underwood’s barbecue.

What all of Spacey’s bad boys have in common is self-knowledge: They know they’re naughty (and worse) but haven’t a qualm in the world. It’s an essential element in any tragic hero: He knows. I can’t imagine any of Spacey’s villains summoning a priest on their deathbeds. Voltaire, no bad guy, was asked to renounce the Devil on his. He’s said to have replied, “This is no time to be making enemies.” So might Francis Underwood remark as he prepares to depart this vale of tears. He’d probably use saltier language.

It is impossible to sufficiently gush over Robin Wright’s performance as President Underwood’s better half—and yes, I am being sardonic. Here is Lady Macbeth, wearing Prada. Actually, I don’t know if it’s Prada, but whatever she’s wearing, Ms. Wright is a stunner in every scene. (President Petrov sure thinks so!) She evinces the malign sexuality of a dominatrix. You wouldn’t be surprised if she showed up at that state dinner for the Russkies in black latex. And she’d look fabulous.

Weirdly, this marriage between an American Richard III and Lady Macbeth manages to be—touching. Francis and Claire have been together for more than 20 years. They may stray a bit, but they’re devoted to each other. I suppose two Gila monsters could also be “devoted to each other.” But this is one political marriage that works.

Of course, it’s much more than just a marriage. Their vows must have consisted of “Scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” I won’t dwell on the fact that House of Cards’ showrunner and principal writer, Beau Willimon, worked on Hillary Clinton’s 2000 Senate campaign as well as campaigns for New York Sen. Charles Schumer and former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean. I wonder: Do his three former employers trumpet their connection with Mr. Willimon? Do they draw attention to it, now that he’s famous for making Machiavelli look like Captain Kangaroo?

Michael Dobbs wrote the novel that inspired the British House of Cards. He had been an adviser to Margaret Thatcher before she was prime minister and, later, was the Conservative Party chief of staff. It was not a warm and fuzzy experience, and it came to an unhappy end. Dobbs and his wife flew to the Mediterranean to chill out. He forgot to pack a book, so he grabbed a paperback off the shelf at Heathrow Airport.

He found it to be complete trash and complained to his wife. She said, “Then why don’t you write one yourself?” He got out a legal pad. By the time the trip was over, the pad contained all of two letters: F and U. When I heard him tell the story, Dobbs hinted that this might have been an unconscious coded message to his wife, from whom he shortly separated. But it was also the initials of Francis Urquhart, the amoral Conservative parliamentary whip. When Urquhart crossed the Atlantic, he became the Democratic whip in the House of Representatives.

As every American television viewer knows, many of our best shows originate in England. When Norman Lear’s fine memoir, Even This I Get to Experience, was recently published, we were reminded that even Archie Bunker of All in the Family had his roots in a British TV comedy called Till Death Us Do Part.

Not all British TV travels across the pond. It’s hard to imagine an American Downton Abbey. But political machination and skullduggery are universal themes. How lucky we are Mr. Dobbs (now Lord Dobbs, if you please) forgot to pack his copy of Middlemarch or Little Dorrit when he bolted for Heathrow that day. How luckier still we are that his accidental novel has been so brilliantly adapted in the U.S.

It’s interesting that the original Urquhart was Conservative. Perhaps the most implausible aspect of all about the American House of Cards is that its hero (as it were) is a…Democrat. I say this as a jaundiced consumer of political TV drama who has sat through one too many shows in which the bad guys are inevitably Republican—villainous versions of It’s a Wonderful Life’s Mr. Potter who chortle and cackle as they gleefully cut welfare benefits to the poor; despoil the environment; reverse Roe v. Wade; enable felons and lunatics to purchase machine guns; and gut financial regulation even as they hustle campaign contributions from Gordon Gekko and the Wolf of Wall Street.

President Underwood, may I say, sir—you are my kind of Democrat.

- On the case with CSI: Cyber, the latest edition of CBS’s crime-solving franchise

- A new direction—and a new threat—on Season 3 of The Following

- Style secrets of Empire‘s fabulous Cookie Lyon

- Shameless‘s Mickey and Ian, TV’s wildest (and sweetest!) couple